When Drug Therapy for Addiction Is Dangerous

Relapse is common for drug treatments—but worse is when people attribute their recovery to them.

This article discusses three kinds of drug therapy in addiction:

- Substitution or maintenance of a less harmful version of the same addiction (e.g., Suboxone, buprenorphine, methadone, nicotine gums/patches)

- Interference with substance effects (e.g., antabuse/disulfiram—which makes drinkers nauseous)

- Antagonists that block the effects of the drug (e.g., naltrexone, an opioid antagonist used with both narcotic addiction and alcoholism)

These drugs have all shown some success in clinical trials. But their limitations are threefold:

- Not everyone responds to the therapy

- Poor compliance (continuation) with the treatment

- The drugs detract from users’ sense of efficacy and belief in their ability to quit or limit use on their own

In general, methadone and buprenorphine (or its commercial form, Suboxone, combining buprenorphine with naloxone, which reduces craving) make it less likely that the person will return to the drug to which they were originally addicted, as shown by this Cochrane Review of buprenorphine. The review did not establish that buprenorphine was life-saving however.

But there is a fundamental problem with substitution, and with all of the other drug therapy. Since all of them reduce the effectiveness of the original drug of choice, people are tempted to quit the therapy and return to the drug—or else to seek a comparable, alternative drug experience.

Thus, most people won’t remain on a maintenance medication. With Suboxone, about 60% of recipients reject the treatment by six months. That figure only increases over time. People quit Suboxone because many simply want to use street narcotics, which many find more effective for addressing their emotional needs or for the experience it provides.

What are the consequences of inexact compliance, let alone total rejection of the maintenance drug? To take one well-known case, when Philip Seymour Hoffman died due to his heroin use, buprenorphine, for which he had a prescription, was found near his body.

So Hoffman is a case where prescribing the maintenance drug was not life-saving. Did the prescription of the narcotic substitute in some sense contribute to his death? That is hard to say. But there are arguments to be made that this could be true.

To take an addiction therapy other than narcotics, Antabuse (disulfiram) is a substance that prevents alcoholics from drinking, since the drug makes people nauseous when they do drink.

But what guarantees that the person will continue to take Antabuse, and what are the consequences if they quit? Part of the treatment protocol in effective therapies, like the Community Reinforcement Approach, is to have a partner or friend ensure that the alcohol-dependent person takes their daily dose of the drug. But that can be a hard row to hoe for the partner.

And will this drug adherence continue for the person’s lifetime? It is usually not clear for how long the drug therapy is to be used, whether it is short-term, in order to wean the person from the substance, or long-term, as the essential tool for lifetime abstinence. Methadone maintenance as practiced tends to be long-term, often for life.

Maintaining lifetime compliance with a drug therapy is another hard row to hoe. Then the question becomes: When a person discontinues their drug treatment, what will be the result? And the answer seems to be a high-relapse rate. This is true for Antabuse—the person stops taking the Antabuse because they want to drink, or even if this is not a conscious decision they make, returning to drinking is still a frequent consequence.

Let’s turn to another drug addiction—nicotine. The most popular medical treatment for quitting smoking is nicotine replace therapy (NRT), either through patches or gum. This is a billion-dollar industry heavily promoted by Big Pharma.

As to effectiveness, in clinical trials, NRT produces a slight but distinct advantage over people’s quitting cold turkey. But, as to maintaining NRT, we then enter the real world. A group of researchers at Harvard’s Center for Global Tobacco Control compared people who quit smoking either cold turkey, or with NRT, three times at interims of two years. (These researchers were on record as supporters of NRT.)

The study found no advantage in smoking cessation from using NRT over the years. Moreover, for the most dependent smokers, NRT use led to relapse twice as often. This typically happened quite early on, when the smokers abandoned their NRT regimen, and then quickly relapsed, even when they received simultaneous counseling. “We were hoping for a very different story,” said Dr. Gregory N. Connolly, director of Harvard’s Center for Global Tobacco Control and co-author of the study. “I ran a treatment program for years, and we invested millions in treatment services.”

Why did highly dependent smokers relapse so readily after receiving NRT?

The most important ingredients in quitting addictions are the belief that you can, and your commitment to doing so. These elements represent a basic life shift; they are inescapable aspects of overcoming addiction in the long run. And these essential ingredients to recovery cannot be injected or ingested in drug form.

Instead, telling yourself that you can’t quit your addiction without the drug undercuts the self-efficacy required to achieve freedom from addiction.

Up to this point, I have been speaking about narcotics that act on the person like illicit narcotics, occupying the same receptor sites. These maintenance drugs substitute for heroin. Nicotine gums and patches—as well as e-cigarettes—provide the same addictive drug as cigarettes, but without the dangers of smoking. That’s a legitimate harm reduction approach, and I endorse it.

Nonetheless, believing that you are an addict who can’t escape your addiction is a downside to such programs. Sometimes, just how serious this downside is can be seen in the research (among the investigators, even more so than the subjects).

A drug used to treat both narcotic addiction and alcoholism is naltrexone. Naltrexone (NTX) is an opioid antagonist—that is, it operates by blocking receptor sites for narcotics, so that the drugs’ effects aren’t experienced.

For some time NTX has been used for treating alcoholism. Although alcohol does not have a specific receptor site, it is thought that the opioid antagonist action of the drug quells the effects of alcohol as well. And good, but often spotty, results have been had with NTX therapy. But this variation in NTX’s effectiveness has prompted speculation and research.

Thus, a team associated with the most prestigious medical research group for addiction—led by Charles O’Brien at the University of Pennsylvania department of psychiatry—tried to clarify why some alcohol-dependent subjects responded well to NTX, and others not at all. Their hypothesis for the study was that two variations of the same opioid-receptor gene either allowed NTX to have its desired effect of blocking the receptor site, or did not facilitate blockage.

O’Brien and colleagues hypothesized that non-responders and responders to NTX had variations (alleles) of the same opioid-receptor gene (also called genotypes). They conducted an NTX trial with 221 alcohol-dependent individuals with these variant alleles.

Here were the results:

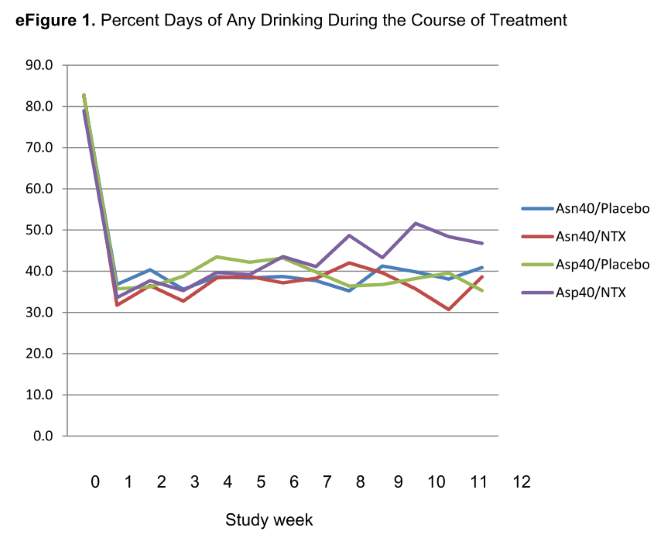

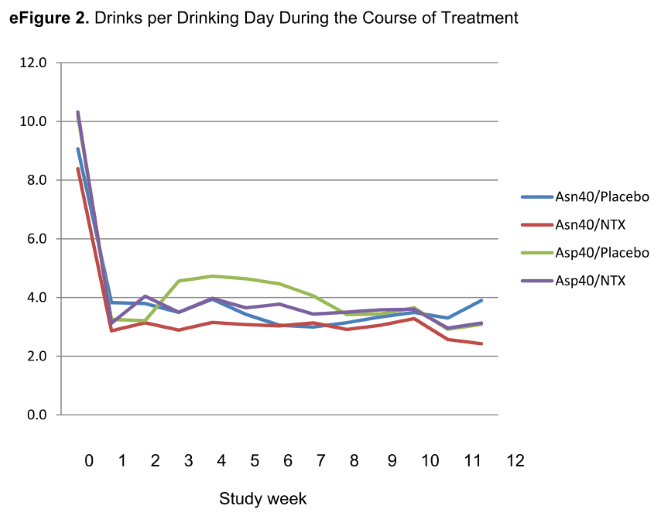

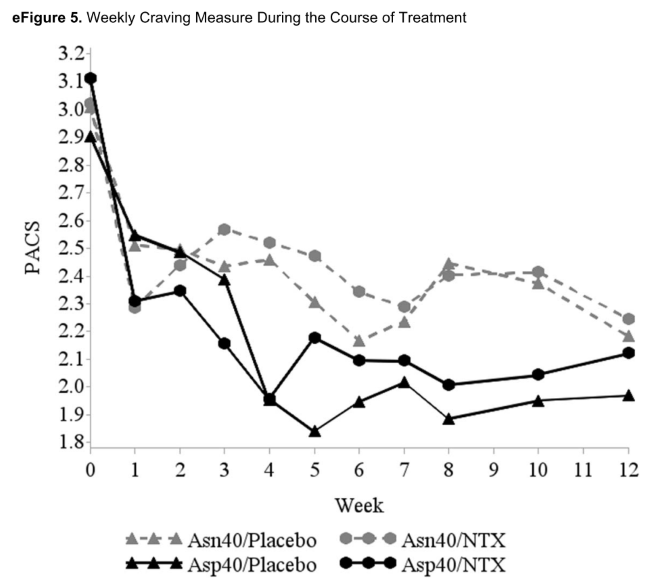

There was no evidence of a genotype × treatment interaction on the primary outcome of heavy drinking (i.e., relapse). In the Asn40 group (one gene variant), the observed effect of naltrexone was similar to that in previous trials. . . A significant reduction in heavy drinking occurred across all groups (that is, with both allele groups and both the NTX and placebo). Other drinking outcomes, and all secondary outcomes, demonstrated similar time effects, with no genotype × treatment interaction.

So, the researchers say, NTX worked as usual for relapse with the one gene group. Oh, but all of the groups, the two with different gene variants, whether they received NTX or they received placebo, reduced their heavy drinking equally! That is, all four groups were virtually identical on all measures: binge rates, days drinking, average daily drinks, and even reported cravings.

But, since the researchers were only looking for a genotype to distinguish responders and non-responders, this is their bottom-line, take-home conclusion: “Despite the results of this trial, pharmacogenetics continues to hold promise as a way to improve the targeting of medications to improve treatment response.” In other words, let’s find another genetic way to identify those who respond differentially to NTX.

But this conclusion makes no sense. The authors are simply showing that mere research cannot remove the blinders with which researchers approach addiction.

This group of medical researchers remains highly committed to the idea of NTX’s effectiveness, and they only want to find out why it works well for some but not others. But, using the best research methodology they could devise—including double-blinding subjects (neither the therapists nor the subjects knew whether they were receiving the placebo or NTX). Subjects who thought they were getting the drug, but weren’t, reduced their binge drinking and drank moderately exactly the same as those who actually received naltrexone.

In order to maximize what they actually found, rather than looking for a pharmacogenetic link, the researchers need to find genes that augment the self-efficacy or responsiveness to placebos that subjects showed, which determined the results of the study. (Note to O’Brien et al.: There are no such genes.)

What this study really demonstrates was completely lost on the researchers. It’s true that one genotype of alcohol-dependent subjects responded as well to NTX as the other. But both genotypes of alcohol-dependent subjects also responded just as well to the placebo, cutting back the percentage of days they drank from 80% of days to 40-50% of days—the higher percentage being true for one of the NTX groups) and from 8-10 drinks daily to fewer than four on those days they did drink. Moreover, all groups reported a large decline in craving for alcohol!

People could cut back their drinking just as well as when they were simply holding onto that feather (i.e., the placebo) that allowed Dumbo to fly!

This is a hard result for us—and the researchers—to fathom: If people can quit or cut back themselves, then why would they need to use the drug therapy in the first place?

Their self-efficacy was a discovery subjects were only able to make because they weren’t given the naltrexone. Indeed, if the blind weren’t removed after the study was completed, they still wouldn’t know that they never got the drug. Or if they learned that they were in the NTX therapy group, they might still think, “Only the drug enabled me to quit.”

But they’re wrong. The bottom line: Everything people need to reduce their binge drinking/alcohol dependence/addiction is already in their minds, ready to be activated whether or not they receive naltrexone by mindfulness techniques. Once the mind is activated, even by fooling people, the drug treatment adds nothing.