How To Fight and Beat Addiction on your own

World-renowned psychologist Dr. Stanton Peele, challenges the conventional 12-step, disease-model approach to addiction, promoting instead a holistic method centered on personal purpose, connections, and a fulfilling life.

He has created the Life Process Program as a ‘non-disease’ approach to recovery. This program, which is now available in an online recovery program, has garnered global acclaim as a compelling alternative to the traditional 12-step method.

In the following guide we provide a comprehensive introduction to the Life Process Program.

We hope it brings you great value!

Table Of Contents:

- Introduction

-

- 1. Self Reflection

- 2. Values: Building on Your Values Foundation

- 3. Motivation: Activating Your Desire to Quit

- 4. Rewards: Weighing the Costs and Benefits of Addiction

- 5. Resources: Identifying Your Strengths and Weaknesses

- 6. Support: Getting Help from Those Nearest You

- 7. Maturity – Growing into Self-respect and Responsibility

- 8. Greater Goals: Pursuing and Accomplishing Things of Value

- 9. Do you want a life without addiction?

-

Introduction

Are you ready to fight and beat addiction?

Fortunately, your being here reading this suggests that you’re ready to accept (or at least consider) a life-change, which is a critical step on the way to recovery.

Of course, you may already have tried to overcome addiction in the past but have found it difficult to keep the momentum going.

If so, then you’re understandably discouraged, but don’t give up! No matter how many times you have tried before, it’s likely that you will achieve the change that you’re seeking – with the right approach and support, you can develop a more healthful and balanced lifestyle.

In fact, you’ll soon see that recovery, even without rehab, is more common than not. Really! And we’ll prove it to you throughout this comprehensive guide on how to overcome addiction.

In short, the way to beat addiction is to make your urge to use or to act on your addiction a secondary (and diminishing) factor in your life – by clarifying, recognizing, honoring and living by your most authentic values that make you who you are.

Admittedly, this is easier said than done (and recovery can be hard work) but the fundamental elements of recovery are well-understood. That’s why we’ve made this guide available to you.

1. Self Reflection

1.1. Recovery is the Rule, Not the Exception

People quit addictions on their own all the time. Evidence for this is all around us.

How many people do you know who quit cigarettes, the most common, and generally considered to be the most powerful, of drug addictions? In the United States, tens of millions of people have quit smoking without treatment, about half of those who have ever smoked.

Surprisingly, the percentage of former heroin, cocaine, and alcohol addicts who have quit on their own is even higher.

The idea of addiction as inevitably a lifetime burden is a myth. How do we know? Because the American government tells us so. In a massive study carried out by the government’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in which 43,000 Americans were interviewed, only one in ten alcoholics entered AA or rehab. Yet three-quarters of people who were ever alcoholic had achieved stable recovery.

The bottom line: three-quarters of those in recovery have been able to fight and beat their addiction on their own.

So it is important for you to know that the independent, self-motivated cure for addiction is possible. In this guide, we hope to show you how to beat addiction on your own and without rehab.

1.2. What Is Addiction?

All addictions follow essentially the same pattern.

Addictions are experiences that can overwhelm a person’s consciousness and which have a net negative impact for the person. People turn to these experiences partly out of the appeal of the specific activity (whether alcohol, drugs, eating, pornography, or gambling etc), partly due to their personal needs and characters (including mental states like depression or negativity), and partly due to the situations they face at the moment. And people tend to tolerate addictions because they lack access to attractive alternatives (more on this shortly).

1.3. Feeling Your Power

Perhaps you’ve heard that people who experience addictions are powerless to change on their own. Not true!

In fact, one thing that enables people to overcome addiction more than anything else: their belief that they are ultimately capable of doing so.

The opposite attitude—believing you are incapable of fighting your addiction and that you are powerless while the addiction is all-powerful—will certainly not help you in achieving your goal.

The Life Process Program stresses that addiction is more overcomable than you know.

To turn your life—or to help turn someone else’s—in a positive direction, it is essential to understand that addiction is changeable and that people often are able to escape addictive behaviors and attitudes as their life circumstances change and as they improve their outlooks and capabilities.

You have been using the addiction as a way of dealing with life, a task you can accomplish in more constructive and non-addictive ways. Now let’s begin drawing the anti-addiction road-map!

1.4. What it Takes to Beat Addiction

People with strong and clear values, and with the motivation to change, are poised to beat addictions (or to avoid addiction entirely).

Likewise, people with friends, intimate relationships, and families; people with stable home and community lives; people with jobs and work skills; people with education; people who are healthy—are well-positioned to avoid or overcome addictions.

So if you are wondering how to overcome addiction, the answer is deceptively simple – You need to seek and gain these life-advantages. When you have such assets, you are helped in overcoming an addiction by focusing on what you have and what you may lose. When you don’t have these things, you may need help to acquire them, (which is what the Life Process Program does).

In addition, you are assisted in fighting addictions by things larger than yourself and beyond your own life. One of these things is the support of those around you and your community. Another is to have and to seek greater goals in life, to commit yourself to be good to other people and to make positive contributions to the world.

Finally, and perhaps most important, you should find this information encouraging and empowering.

Self-empowerment is the most potent addiction antidote of all.

In the sections that follow, we will detail how you may accomplish these things.

This guide provides a road map to self-improvement. It is a tool that you can use to examine your own life, non-judgmentally, noting what you have and what you lack, in terms of the skills and resources you need to beat addiction.

1.5. Addiction is not a disease

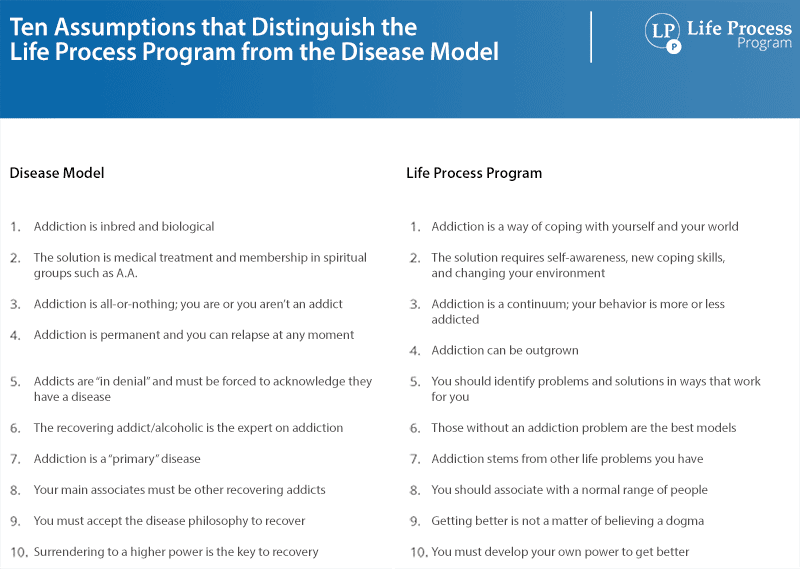

The following table summarizes ten assumptions that distinguish our approach from the Disease Model of Addiction:

We believe that many people want an open-minded, realistic way to understand and deal with addictions—their own, their spouses’, their children’s, their friends’ and employees’. This guide is a response to that need.

Addiction is a learned and ingrained habit that undermines your health, your work, your relationships, your self-respect, but that you feel you cannot change.

Addictions are difficult to change, because you have relied on them—in many cases for years or decades—as ways of getting through life, of gaining satisfaction, of spending time, and even of defining who you are. Whereas some addictions involve drugs (like smoking or problem drinking), some do not (like shopping, or eating, or sex). It is impossible, therefore, to relate addiction to a chemical or biological process.

Because of the distinctive approach we take, you will find guidance here that in most cases you cannot get elsewhere.

That is, we do not regard addiction of any kind as a disease. Thus, we do not recommend that you see a doctor or join a twelve step group organized for one disease or another as a way of dealing with addiction.

These approaches, we believe, have already been shown to be less effective than others that are available. In fact, many addiction rehabilitation facilities—where these approaches are regularly practiced—do more harm than good.

Our approach for changing destructive habits, called the Life Process Program, is instead rooted in common sense and people’s actual experience.

This approach is more empowering—and therefore more effective—than conventional treatment or self-help methods. The good news is that many people are beginning to question how accurate or helpful it is to think of addiction as a “disease.”

The disease model of addiction does more harm than good because it does not give people enough credit for their resilience and capacity to change.

It underestimates people’s ability to figure out what is good for them and to adapt to challenging environments. At the same time, it disempowers people, because it fails to hold them accountable if and when acting irresponsibly while under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or for excessive non-drug habits ranging from shopping to gambling.

The disease theory of addiction can even perpetuate addiction.

Our approach, in contrast, respects every person’s capacity to improve and to make positive choices, even in the case of the most compulsive behaviors. Instead of undermining your integrity, we give you credit for being a responsible adult capable of self-management.

The Life Process Program takes us far from the frightening assumption that a compulsive behavior is a disease that you will have to live with forever. Remember: millions of people have quit smoking (the toughest drug to quit) in the United States alone. My uncle was one of these people.

1.6. Introducing My Uncle Ozzie

My Uncle Ozzie was born in Russia in 1915 but came to the United States as a small child. As a teenager he developed an addiction to smoking. Outwardly calm, Ozzie did not have obvious reasons for smoking. Nonetheless, he continued to smoke into the early 1960s. But Ozzie quit smoking in 1963, the year before the surgeon general’s 1964 report making clear that cigarettes cause cancer.

I didn’t actually notice my uncle had quit until years after the fact, when I saw him at a family gathering when I was home from school, after I became interested in the question of addiction. I asked him, “Ozzie, didn’t you used to smoke?” Ozzie then told me his story.

He began smoking at the age of eighteen and continued smoking for thirty years. Ozzie described his smoking as “a horrible habit”—he smoked four packs a day of unfiltered Pall Malls. He kept a cigarette burning constantly at his workbench (Ozzie was a radio and TV repairman). He described how his fingers were stained a permanent yellow. But, he said, until the day he quit, he had never even considered giving it up. On that day the price of a pack of cigarettes rose from thirty to thirty-five cents.

While eating lunch with a group of fellow employees, Ozzie went to the cigarette machine to purchase a pack. A woman co-worker said, “Look at Ozzie—if they raised the price of smokes to a dollar, he’d pay them. He’s a sucker for the tobacco companies!”

Ozzie replied, “You’re right—I’m going to quit.”

The woman, also a smoker, said, “Can I have that pack of cigarettes you just bought?” Ozzie answered, “What, and waste thirty-five cents?”

He smoked that pack and never smoked again. A few years ago, Ozzie died. He was over ninety years old.

Why did my uncle Ozzie quit? To understand that, you’d have to understand what kind of person he was. Ozzie was a union activist and shop steward. Adamantly left-wing, he was a man who lived by his beliefs. It was Ozzie’s job to stand up for any worker sanctioned by the company. As a result, he believed, he was punished for his activism by being sent out to the worst parts of the city on television repair calls.

Why did Uncle Ozzie quit smoking that one day, after thirty years of constant, intense smoking? He had never previously considered quitting, but less than twenty-five words thrown out by a blue-collar colleague somehow caused him to drop the addiction. We will return to this question in the next section, but for now it is enough to recognize that he did it.

2. Values: Building on Your Values Foundation

When you can truly experience how a habit is damaging what is most important to you, the stepping-stones away from your destructive habit often fall readily into place.

2.1. What Are Values? Do they really matter?

Your values are your beliefs that some things are right and good and others wrong and bad, that some things are more important than others, and that one way of doing things is better than another. Values are usually deeply held—they come from your earliest learning and background. Values reflect what your parents taught you, what you learned in school and religious institutions, and what the social and cultural groups you belong to hold to be true and right.

Values are important to all addictions, and not just addictive drinking and drug taking. If you gamble compulsively, watch porn or live out your life on Social Media to the exclusion of your life off-screen, then your values are on display. The same principle applies to pursuing sexual opportunities to the exclusion of productive activity. Most people enjoy sex, but they avoid compulsive or random sex because they feel it’s wrong. If you engage in indiscriminate sex, then you are signalling either that you see little wrong in it or that the other values in your life are less important than the good feelings you derive from such sex. If you are willing to accept this picture of your values, then so be it. If, on the other hand, you have other values that run against compulsive sexual activity, eating, or shopping, then these values can serve as an important tool with which to root out your addiction.

Many people find that alcohol is tremendously relaxing, sexually exhilarating, or provides some other powerful, welcome feeling—but they do not become alcoholics. They simply refuse to go there. Have you ever heard someone say, “I know that when I have more than one drink, I throw all caution to the wind”? Most people who react so violently to alcohol say, “That’s why I limit myself to a single drink” or “That’s why I don’t drink.” But those addicted to alcohol regularly override this realization about their reactions to alcohol and continue to drink.

Some values directly contradict addictions. If you have these values, they help you to fight addiction. And if you don’t, developing such values is potentially a critical therapeutic tool. Values can be expressed by statements about what you think is right and wrong, or about your preferences, such as:

- “I value our relationship”

- “I value my health”

- “I believe in hard work”

- “Nothing is more important to me than my children”

- “It is embarrassing to be out of control of yourself”

All of these values oppose addiction. An absence of values, can reinforce addiction. For example, if you don’t think that it’s wrong to be intoxicated or high, if it’s not important to you to fulfill your obligations to other people, or if you don’t care whether you succeed at work, then you are more likely to sustain an addiction.

2.2. How Do Values Fight and Beat Addiction?

To say that your values influence your desire and ability to fight addiction is to say that you act in line with what you believe in and what you care about. Such values can be remarkably potent. For example, I heard a woman say,

“I used to smoke, and sometimes I think of going back to it. However, now that I have small children, I would sooner cut my fingers off with a kitchen knife then start smoking again.”

Even if this woman fell to temptation and smoked one cigarette, it is highly unlikely that she would relapse entirely. Observing this new sense of identity and resolve in new parents should make you think, quite sensibly, “This person couldn’t be addicted to drugs or alcohol; she cares too much about herself and her family.”

As a society, and as individuals, we need to grasp that there is no more important facilitator or antidote to addiction than our values. For example, people who value clear thinking will shy away from regular intoxication. Likewise, a responsible person highly concerned for his family’s well-being would not allow himself to shop or gamble away his family’s money. People who are focused on their health will be reluctant, or refuse, to drink excessively or to take drugs.

Consider some values you can discover within yourself that run counter to addiction. Consider how much you value:

- Self-control and moderation. Some people simply will not permit their lives to get out of control. They cannot imagine themselves reacting automatically to some external stimulus. Instead, they regulate their behavior according to their own values, principles, and purposes. These people may be repulsed, amused, or sympathetic when they observe someone else who drinks too much, or who cannot refuse an extra helping of food. But if you value moderation, you don’t tolerate this for yourself and are reluctant to accept it in the people close to you.

- Accomplishment and competence. Addiction is much less likely to sidetrack those who value achievement and who revel in their mastery and exercise of life skills. College students become addicted to cocaine and alcohol only rarely compared with deprived, inner-city people, because they have other plans for themselves with which addictions interfere. Even with the stresses and minimal rewards of student life, they are exercising skills and looking forward to greater accomplishments. If you do not value achievement and do not see accomplishment in your future, establishing the desire and the hope that you can achieve substantial goals is pre-eminent in eliminating addiction.

- Self-consciousness and awareness of one’s environment. Some people place more value than others on being alert and aware. For many people addicted to drugs, such self-consciousness is actually painful, and drugs are the best remedy for this pain. Addiction will readily follow if a person strives to eradicate the pain of consciousness. The alternative is to value awareness and to believe that such awareness pays off—that if you are awake to your environment you will get more from it. You are also less likely to be addicted if you have faith that thinking about a problem will lead to a solution, and that blinding yourself to reality will get you into a deeper hole.

- Health. What keeps most people from persisting in damaging addictions is the basic human instinct not to hurt themselves. Some individuals, on the other hand, don’t care much that they are harming themselves: that they are battered, or destroying their lungs, or reducing their mental capacity. To tell a hard-drinking, hard-smoking, tattooed sailor (or, in many cases, a young drug and alcohol abuser) that his behavior is harmful often doesn’t make much of an impression. This is because he doesn’t see health as a value to pursue and maintain. If, however, your physical well-being is a personal priority for you, you will be likely to give up or moderate your addictive habits.

- Self-esteem. Self-esteem protects against addiction in two ways: first, by reducing your need for habitual escape or consolation; second, by stopping you from destroying yourself. Addictions and drug and alcohol abuse are like mini-suicide—killing yourself a little each day. An adult who tolerates being put down or beaten may feel she doesn’t have the right to reject these assaults. Many who fall short of this degree of self-hate still don’t value themselves. And self-destructive behavior is a natural outgrowth of this negative self-image. You can resist addiction, on the other hand, if you understand that it is wrong to be beaten and put down and that you deserve to be treated well. The more you value yourself, the less you want to be addicted, and the less likely you are to let yourself be addicted.

- Relationships with others, community, and society. Most addictions are antisocial. For starters, they involve an over concentration on oneself and one’s feelings. Addictions are a kind of dark, inverted version of self-esteem. People experiencing addiction may not always care about their own health and well-being, while still so self-preoccupied that they hurt others as much as or more than they hurt themselves. Addictions often require ignoring societal values. When you hear of a mother who locks her children in the house while she goes out to score drugs, or who locks herself in her bedroom to get drunk, or who prostitutes her children; or of a father who wastes all his money gambling, or who regularly falls down drunk in front of his children, or who beats them as well—you are talking about people whose values support the most destructive addictions.

These values are a kind of unrealized strength that you can summon up: to the extent that you possess them, you are less likely to become addicted in the first place and are better able to surmount addictions that do develop.

2.3. Returning to my Uncle Ozzie

My Uncle Ozzie is a prime example of a person whose values helped him beat addiction. As you will remember, Ozzie quit smoking forever based on what seemed like a chance statement by a co-worker that Ozzie was “a sucker for the tobacco companies.”

We are now prepared to answer the question of why Uncle Ozzie quit.

Remember that Ozzie was a committed union activist. The most important value governing Ozzie’s life was the desire to maintain his integrity and independence from his employer, who symbolized for Ozzie the entire capitalist system. As a shop steward, he regularly demonstrated the strength of his convictions by pressing worker complaints and defending fellow union members, even though he felt he was punished by being sent out on service calls to the worst neighborhoods.

Intentionally or not, Ozzie’s co-worker’s statement that he was a sucker for the tobacco companies hit Ozzie in his value solar plexus. This colleague made Ozzie see a connection between his anti-corporate values and his smoking, producing the revelation that smoking ran counter to his overwhelming desire to be free from company control.

When Ozzie realized that smoking compromised the most important element in his self-definition. . . well in that moment smoking didn’t stand a chance.

After finishing the last pack he purchased, Ozzie never smoked again.

2.4. Identifying Your Values

To further assist you in identifying your core values, list the three worst losses you could suffer in life, such as:

- Your health

- Your family or life partner (or their approval)

- Your appearance

- Your relationship to God

- Your intelligence

- Your standing in the community

- Your self-respect

- Your job/profession/work skills

- Your friends

- Your ethical standards

- Something not mentioned above

Make a list of how your worst habit is affecting these three things. Now describe a way that you can keep focused on each of these values as leverage to change your addiction.

3. Motivation: Activating Your Desire to Quit

The simplest answer to the question “When do people change?” is “When they want to.” No amount of science, therapy, and brain scans is ever going to change this truth.

3.1. The Role of Motivation in Change

AA considers willpower to be utterly ineffective. The idea that people have the commitment and power to be able to change on their own (without the help of AA, a “higher power,” and other AA members) is anathema to the group. Yet what is it, if not willpower or motivation, that makes some people join, stay with, and succeed in AA?

Wanting, seeking, and believing that you can change do not necessarily translate into immediate success. The fact that Uncle Ozzie could do it in one shot does not mean that you will do it that way. It is much more common for people to make several attempts before successfully quitting their addictions. Indeed, this persistence is a sign that you really want to quit.

It is true that repeated failures are demoralizing and may signify that you need to try something new. It can also mean that you have simply not been in the right place in your life to change, and that you need to do more groundwork. The Life Process Program can help you begin to lay that groundwork.

While setbacks can be discouraging, don’t get down on yourself for your inability to instantly transform into the person that you want to become. Addictions have roots deep in your lifestyle, outlook, and personality, and beating them will naturally take a concerted, complex effort. Demoralization is much more harmful to the recovery process than being over optimistic.

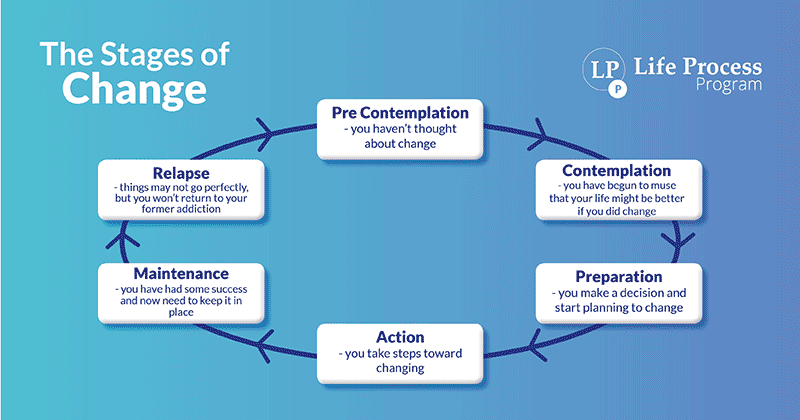

3.2. Stages of Change

The motivation to change takes different forms, depending on where you are in your addiction cycle. Some people have to be introduced to the idea that they need to change. Others have spent a lifetime fighting to change. One widely used scheme for organizing the stages of change was devised by psychologists James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente:

Stages of Change

- Precontemplation—you haven’t thought about changing

- Contemplation—you have begun to muse that your life might be better if you did change

- Preparation—you make a decision and start planning to change

- Action—you take steps toward changing

- Maintenance—you have had some success and now need to keep it in place

If you are reading through this program, you have probably already decided you want to change, and are at least at stage 2 of the process.

3.3. Effective Treatments for Addiction

Much research has been done on the most effective treatments for addiction, particularly alcohol addiction. The two best treatments for alcohol addiction rely on putting the ball on the alcoholic’s side of the court, helping the addicted person channel his or her own motivation into successful change: Brief Interventions and Motivational Interviewing (or Motivational Enhancement).

3.3.1. Brief Interventions

When you have a physical exam, your doctor might ask you, “How many drinks would you say you have in a week? Do you drink about the same amount each day, or do you drink mostly on weekends?”

This ostensibly casual screening and assessment would be followed by feedback: “You know, for most men your age, the healthy limit is two or three drinks a day,” or “You have identified several problems stemming from your drinking,” or “You are having some difficulty with your liver; let me show you on this test.” As in any health care encounter, a doctor would discuss your general life and health problems, and pursue their relationship to your drinking.

The procedure is conducted neutrally, like any other impartial medical assessment. The physician or other health care worker then initiates a conversation about steps to lower risk, which, in Brief Interventions for alcohol, usually means reducing your drinking from an unhealthy level.

Following the feedback from the assessment, the physician may simply advise you to cut back. Alternately, the physician may say something like:

We meet again in X months, on such-and-such a date. What goals do you hope to achieve when we meet again? How many drinks do you plan to be having daily/weekly at that time? What do you need to do to make sure this happens? Here are some of the services this office can provide for you. Do you feel any could be helpful to you? I also have some brochures for you that contain information about ways people go about reducing their drinking and other information on alcohol. Are there ways you feel your wife can be helpful, without shifting the burden to her?

Note that the doctor provides suggestions, options, and self-help material for the person to follow through with. Although the doctor provides structure and feedback for change, the manner in which you decide to tackle the problem is up to you.

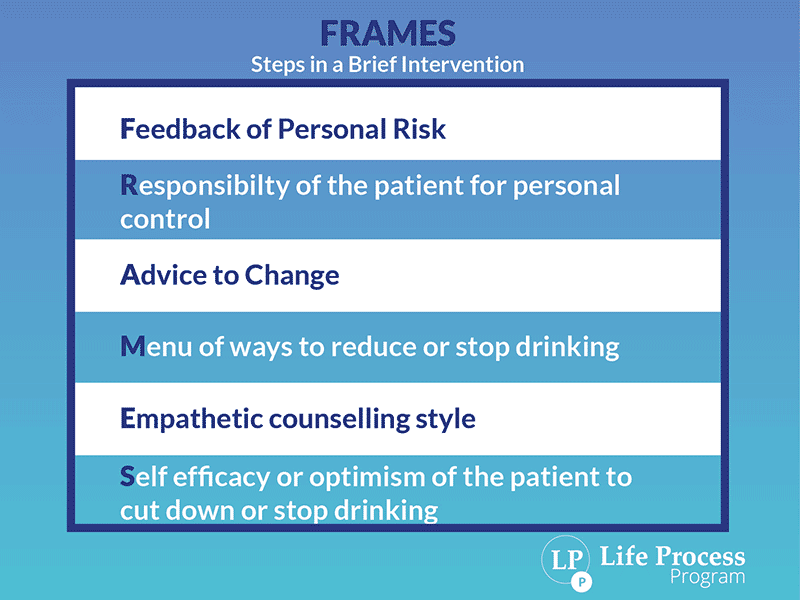

How can you harness the assets of a BI in your own recovery process? The critical elements for change in BIs are as follows:

Critical Elements of a Brief Intervention

- A nonjudgmental atmosphere where you can focus on your problem in a calm, non-defensive way.

- Your acceptance of the need for change.

- Provision of suggestions and options, which you can choose among and combine into your own course of action.

- The un-intrusive support of the adviser or health care worker.

- A process that engages your commitment to and responsibility for change,

- Regular follow-ups when you know your progress will be monitored.

William Millar developed a mnemonic for remembering the key elements in Brief Interventions:

_______________________________________________________________

THE BRIEF INTERVENTION PROCESS (FRAMES)

F: Feedback about risky behavior is given

R: Responsibility for change is placed with the individual

A: Advice is given to change

M: Menu for change options and methods is presented

E: Empathy is expressed

S: Self-efficacy is encouraged

______________________________________________________________________

One powerful aspect of the Brief Intervention process is the continuity of contact (like that which we provide in LPP). That is, the regularity and extent of follow-ups may be the most effective aspect of a treatment. Remaining in touch with a concerned third party who provides you with objective feedback focuses you on your behavior and your desire to change it. It is very helpful if you have someone you can rely on, who wishes the best for you, but who is not as emotionally involved as a spouse usually is, and so can objectively record your successes and failures.

The Brief Intervention approach emphasizes that the counselor will keep in touch to encourage and respond to appropriate behavior, even when it takes you a while to activate the behavior you know is better for you.

3.3.2. Motivational Interviewing

People respond best to therapeutic inputs when they are approached with respect and empathy. This simple truth is often lost in therapy. Think about it: How do you react when someone bombards you with feedback that you’re completely off base and all wrong in your approach to something? Most often you won’t react well. If, on the other hand, people begin by respectfully considering your point of view and accepting your sincerity, you will most likely respond to insights and suggestions they offer you.

People overcome addictions when they realize that it is in their own best interest to do so. The goal of Motivational Interviewing is to get people to examine their habits in terms of their own values and goals. Likewise, you are most likely to change when you can see yourself and your own actions in this light.

Motivational interviewing is a counseling method that helps people resolve ambivalent feelings and insecurities to find the internal motivation they need to change their behavior. It is a practical, empathetic, and short-term process that takes into consideration how difficult it is to make life changes.

Suppose a high school student wants to be successful, to make money, and to achieve high status—like most people. Yet his or her behavior, including drinking and drug use, is making this goal less likely. A parent or helper could give this child a standard lecture: “If you think you’re going to be a success, think again. Don’t you see you’re headed down the road to nowhere?” This is the typical style of interventions and of secondary school prevention programs.

What if, instead, the parent or other adult asked the teenager about his or her goals—“What do you want to achieve in life?”—and then examined the child’s progress in this direction in a non accusatory way? The adult could ask the child to think about the kinds of people he or she admires—probably high achievers who didn’t create roadblocks for themselves, then let the adolescent reflect on what that says about him or herself.

A person conducting such a motivational interview should keep the following elements in mind:

1. Express empathy (“I accept that you are a valuable person”)

2. Explore values/goals (e.g., “What do you want for yourself?”)

3. Develop discrepancies (“How are you going about this?”)

4. Roll with resistance (“I accept everything you say”)

5. Support self-efficacy (“You can achieve what you want”)

If you are concerned about someone and would like to try reaching out to that person using the MI approach, the aim in this kind of questioning is never to place yourself in direct conflict with the target. Whenever you sense resistance, back up. The key to this approach is to push the ball back to the other person (generally by asking questions), even when you feel you know what the truth of the matter is. And, despite your deeper purposes, you should mean it when you make these into questions.

You must leave the answers up to the person you are questioning. Suppose a man has come to speak about his wife’s objections to his drinking. Instead of immediately assuming the man has a problem and taking the wife’s position about the man’s drinking (whether or not this ultimately turns out to be true), the questioning might go like this:

Man: My wife is always griping that I drink too much.

Questioner: And how does her griping affect you?

Man: It’s a real pain.

Questioner: So you want to do something about that. And what makes her think you drink too much?

Man: She just doesn’t like me drinking. So when something happens—like when I fell asleep drunk on the couch—she freaks out.

Questioner: Do you think you drank too much that time?

Man: Well, yes . . .

Follow-up questions could include: “Describe any other times you may have drank too much.” “Did an interaction with your wife spur that episode?” “How does your wife generally react when she thinks you’ve drank too much?” “Do you anticipate she will react this way when you start to drink?”

The goal of this questioning is not to judge the man, but to understand the link between his drinking and his relationship with his wife. Exploring this link through questions may well reveal patterns in his relationship that make sense to him, as well as ways to change and improve it and his drinking, without putting him on the defensive.

Motivational Interviewing is a way of holding a mirror up to people so that they can see that they are defying their own feelings and values. This helps them to bring their behavior in line with who they want to be. But, as I have said, you can at the same time be performing this service for yourself.

Holding up a mirror to others’ thought processes and motivations can also hold a mirror up to your own. While you are assisting them to see into the self-defeating contradictions that often characterize human thought and action, you can simultaneously become aware of these conflicts in yourself and move to change in a positive direction.

4. Rewards: Weighing the Costs and Benefits of Addiction

If motivation is the force that drives you to act, then rewards are what you gain from that activity. People quit their addictions when they begin to get more rewards for living without the addiction than they got from feeding the addiction. Put into economic terms, you give up your habit when you believe that its costs exceed its benefits.

Of course, the nature of rewards is highly subjective. You incur all sorts of costs from an addiction—health, financial, legal, interpersonal, and so on. However, you also are getting benefits from it—rewards that often loom larger than life because they are so immediate and familiar to you.

4.1. The Rewards of Addictions

Excessive alcohol consumption, eating, and sexual activity etc provide you with feelings and sensations that you desire and need. Some of these essential feelings are a sense of being valued, of being a worthwhile person, or of being in control. It is critical for you, or anyone trying to help a person with an addictive problem, to understand the needs that the addiction fulfills. This understanding is necessary in order to root out the addiction.

However, addictions don’t really provide people with positive experiences or benefits. Although they provide short-term or illusory rewards, addictions ultimately lead to negative feelings and life outcomes. In the long run, you are worse off as a result of your addictive behaviors.

Moreover, over time, addictions take on their own momentum. Once you get used to relying on your addiction, your whole life begins to revolve around it, and your indulgence in overeating, drinking, smoking, shopping, or gambling becomes the first place you turn when you are under stress or simply looking to please yourself. You lose focus on how the addiction is damaging you—you begin to take the sensations and rewards it offers you as a given, as though you had no other way to obtain them.

It is these short-term and habitual rewards in your addiction to which you are attached. And people are simply not ready to give up these benefits until they find an alternative source of satisfaction. The task for you, in order to overcome any destructive habit, is first to get a handle on why you turn so regularly to the same sensation or experience—what you get from the addiction and the role it serves in your life. Examining what underlies the addiction will help you to get your automatic responses under control. Only then can you identify how you can find superior, non-addictive rewards to take the place of the addiction.

4.2. Are Addictions Pleasurable?

Most people assume that drug use is inherently rewarding—which is the position taken by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. That is, people take it for granted that drugs such as cocaine and heroin are so pleasurable that it is almost impossible to resist them once you have tried them. However, we have seen that this is not the case.

In fact, people resist the pleasurable effects of drugs as a matter of course. For example, most people who at one point took heroin or cocaine no longer do so. Even addicted users, like some Vietnam vets who became dependent on heroin, quit or taper off when their lives permit them to pursue a normal range of rewards.

4.3. The Rewards of Work and Family

Family and work responsibilities are two of the most powerful experiences human beings can have, and their rewards regularly outweigh the benefits provided by drugs, alcohol, and other addictions. While you may not be a genius at work, you probably limit your addiction because of your professional obligations. Odds are that you already take steps to make sure that your addiction doesn’t interfere with your livelihood. Perhaps it worries you that you sometimes daydream about gambling, or going out for a smoke or a drink. But that you don’t is what the fight against addiction is all about. This resistance to your impulses demonstrates that you already have the means to control your habit under the right circumstances. The next step is turning that control into normal self-reflexive behavior — tipping the scale of addiction.

4.4. Tipping the Scale of Addiction

It is important to recognize the way in which we often substitute the rewards of alcohol and drug use and other addictions for the rewards we lack in our everyday lives. When you think about the benefits that you receive from the addiction, think of a weighing scale, with the reasons for using on one side. Now let’s focus on the other side of that scale. What are the costs, the negatives, of your addiction?

In tipping the scale, we need to keep in mind the different stages of addictive behavior change. Some people benefit from help seeing that they should quit their addiction, or that their habit is an addiction in the first place. Sometimes simply considering this idea of a scale, with its enumeration of all the negative effects of the habit, helps people gain the insight that change is necessary.

As you read this, you may already have decided that you want to change. The issue that you face is how to establish new behaviors and how to maintain them over the course of your non-addicted life. In order to do so, it will be helpful to keep this scale of costs and benefits in mind. It will motivate you to change, and it will keep the change in place in the years to come.

Procrastination

Many of us are waiting for just the right moment to change, when the costs of the addiction are so great that change is unavoidable. We can imagine the perfect situation for kicking the addiction; we’re just not there yet.

Jeff, for example, is an affable thirty-year-old smoker who would like to start a family. He expects to quit smoking after he gets married. In fact, he actually has an elaborate fantasy that this will occur because he will marry a smoker, and she will be forced to quit smoking when she becomes pregnant, dragging him along with her.

Given his intelligence and strong value system, it would seem that Jeff would have enough motivation to change on his own now. That is, if the idea of having a wife and children is so appealing to him, then Jeff should quit smoking as a way of pursuing the family rewards that he seeks. In fact, it makes the most sense for him to begin dating a non-smoker, who would insist he begin the process of quitting smoking immediately. Instead, by setting up such an elaborate scenario in his head, Jeff is creating an out that keeps him from having to fight his addiction. This is the danger of picking your rewards so specifically that they actually stand little chance of occurring. You can get started now, and beat Jeff to the recovery path.

Traumatic Event

Maybe you are waiting to change until you have a heart attack, you develop diabetes, you go bankrupt, or your spouse leaves you. You figure that this will resolve all your hesitance or ambivalence. Once one of these things happens, then you will know that you have to change. Perhaps you have seen how famous people use catastrophic situations as reasons to fight addictions, and you want to follow in their footsteps.

But there are serious drawbacks to waiting until you are on the operating table to decide to change. Sometimes you die. Sometimes an ailment is irreversible. Or in terms of substance misuse, you can permanently damage your health, lose your family, or even end up in jail! But you don’t have to wait to “hit bottom” to change.

Instead of waiting for something awful to happen to tip your cost-benefit scale, it is more useful to visualize these negative outcomes before they occur. In this way, you can use controlled fear to modify your current behavior.

4.5. Replacing Rewards

When you examine the rewards reaped through your addiction, you will often discover that they are weak and/or illusory. That means that you should seek out healthier ways to get the same needs met. As you keep in mind the negative consequences of addictive rewards—the weight gain, the cost, the intoxication and hangovers, the recriminations and guilt—look for superior ways to gain each supposed benefit of your addiction. For example, if you turn to alcohol, cigarettes, or food to help you relax, then you might try exercising, doing a guided meditation, or getting a massage. If you seek excitement and satisfaction through gambling, shopping, or drugs, think of rock climbing, starting a business, or volunteering at a charity.

Obviously, some gratifications provided by an addiction will be easier to replace than others. Filling an empty place because you don’t feel loved or you don’t have a purpose in life is going to require major life refocusing. At the other extreme, eating, drinking, or gambling because you are bored is a more straightforward problem to solve.

Think about the benefits of your addiction when it first began, and compare these to the benefits that you seek now. How have your rewards shifted? Have they become more or less pleasure-oriented? Do you engage in your addictive activity in order to seek positive sensations or in order to drown out negative ones? Think now about how the costs have changed over time.

For every benefit of your addiction that you list, find three alternative ways you can gain these feelings, satisfactions, or experiences.

5. Resources: Identifying Strengths and Weaknesses, Developing Skills to Fill the Gaps

Overcoming addiction requires you to evaluate your strengths and weaknesses and to address your weaknesses effectively. This involves two related sets of activities:

- First, you need to assess what resources you already have and what resources you currently lack.

- Then you need to develop the skills that will allow you to expand your resources. Moreover, these skills themselves are critical in overcoming addiction.

Not all people are created equal in terms of kicking addictions. You might think, “Sure, I could lose weight if I had a personal trainer and chef like Oprah and those Hollywood stars.” However, compared to someone else who can’t afford a health club membership, you may be in a relatively good position to get in shape. Take someone working at a marginal job—say, a single mother who waitresses. What does she do during a break or following work in order to relax? Smoking seems like the cheapest, easiest relief she can turn to, while a better-off person might take an aerobics class.

Research shows that the more resources people have and develop, the more likely they are to recover from addiction. Resources are not limited to money. Here are key assets in fighting an addiction:

Key Assets in Fighting Addiction

- Intimacy and supportive relationship

- Marriage and family relationships

- Friendships, groups

- Employment and work resource

- Work skills and accomplishments

- Leisure activities

- Hobbies and interests

- Exercise and relaxation

- Coping skills

- Practical skills

- Social skills

- Emotional resilience and ability to deal with stress

These personal assets are a better predictor of recovery than wealth. But how do you develop these resources if you don’t already have them? And how do you use them to fight and beat addiction?

5.1. Assessing Your Strengths and Resources

Look at your life and take inventory of your strengths. What are your greatest accomplishments in life? What are you good at? What do you enjoy doing? What do people like about you? What big changes have you made in your life? What resources do you have at your disposal? Some possible answers to these questions are:

- I quit smoking.

- I am good at home repairs.

- I am well organized.

- I am smart with money.

- People like my friendliness.

- People turn to me in crisis.

- I have always held a job.

- I have good relationships with my children.

These and other successes like them may seem like small triumphs. But none of these abilities can be taken for granted. Some people desperately need to organize their lives. Many need to learn how to deal with stress. Few people cannot benefit from improving their communication skills, and some people have great difficulty communicating even their basic needs to other people. The fact that you’re already gifted in any of these areas means that you are that much closer to beating the addiction or negative behavior that concerns you. Many people would envy your resources!

Identifying existing resources can be energizing and inspiring. You, too, have strengths you should be proud of. If you are well organized, practical, or gifted at household repairs, then similar problem-solving abilities will work in other areas of your life. These abilities should inspire you with confidence and give you faith that you can accomplish more. Picture yourself in your most confidence-inspiring setting and try to maintain that confidence while working on the rest of your life. When you can see yourself in your best light, then you will be the most confident about combating your addiction. As you chronicle your existing resources, you can at the same time assess your weaknesses. By appraising your skills, you highlight the ones that are missing. These are skills that you may need to develop in your effort to beat your addiction.

5.2. Developing the Essential Skills to Beat Addiction

We can identify the skills that have been found to be most critical to the recovery process. These include social skills, which enable you to deal with people and life (communication, problem solving, and being alone); managing emotions, dealing with the emotional states that drive you to resort to addictions; and resisting urges, dealing with impulses to turn to cigarettes, food, shopping, or other harmful habitual responses when faced with stressful situations.

Even after people have been drug/alcohol/(other)-free for a time, they need to learn how to break the cycle that compels them to resort to their habit. The skills needed to interrupt this cascading series of events are collectively labeled relapse prevention.

We will now look at each of these in more detail.

5.2.1. Communication

Communication is the building block of professional and personal relationships. In these and other arenas, you need to take in information and present information to others. You need to feel secure enough to listen to things that may be unpleasant, without shutting off or striking out at the messenger. When presenting information to others, you need to want honestly to convey concrete information, rather than to put the other person down or make yourself feel good.

An inability to allow genuine feedback from one’s partner is a trait of relationships with problems; often it accompanies substance or spousal abuse. Learning effective communication techniques (including between partners in a couple) is a critical element in resolving addiction.

Communication skills can be taught, and you can improve them on your own. In order to communicate effectively, you must first create a positive tone. Point out positive things your partner is doing, perhaps in response to requests you previously made. Next, identify the specific problem concerning you. Don’t make global criticisms, but describe how the problem affects or bothers you. Then solicit the other person’s reactions. Try to imagine how the other person feels. Acknowledge how your actions feed into the problem. Ask for ways that you can help your partner to change. The same communication principles apply to marital communications, those between parents and children, and those with other relatives or co-workers.

5.2.2. Problem Solving

If you don’t feel up to meeting life’s challenges, you may rely on drugs, food, or sex as a way to anesthetize yourself against anticipated failure.

In place of this defeatism, which contributes to the failures that you anticipate, you can learn methods of coping with problems. The essential ingredient in problem management is remaining calm and sensible. You must gain confidence that you will be able to deal reasonably with the problem.

This does not mean you can always reach a perfect resolution. It does not mean that the problem will disappear. It does mean that you feel capable of coming up with a reasonable response. This is inspiring rather than depressing—depression is the condition that results from believing you have no avenues open to you when a problem arises.

The first step in problem solving is to identify the problem—framing it in manageable terms, so that it does not seem overwhelming and frightening. Don’t let self-criticism (“I always end up in this situation”) or self-defeating thoughts (“I’m not strong enough to deal with this”) demoralize you. Rather, focus your thinking in a positive direction. You may say to yourself, “The last time I got into this situation, I had no idea how to deal with it. Now I have experienced and dealt with it, and understand what to do. I know I can get through this successfully.”

Making a problem manageable so that you can tackle it can mean breaking a larger problem into component parts. If you are leaving a relationship, for example, you have to see to your emotional well-being, find a place to live, seek social support, and arrange a number of other parts of your life. Thinking globally that your life as you know it is over is not a good starting point for tackling these issues.

With a good fix on your problem, you can begin to seek out needed information and evaluate possible options. After selecting an option, your goal is to commit yourself to the course of action while simultaneously being open to feedback about whether that course of action is workable and successful.

Finally, keep in mind your growing body of success at solving problems, a résumé that you will lengthen each time you apply this structured approach.

5.2.3. Independence and Being Alone

Addiction is nearly always tied to relationship problems, to the absence of or search for intimacy and companionship. When people are alone, they turn to every type of compensatory excess: drugs, alcohol, shopping, eating, TV, gambling, and so on.In order to avoid being alone, they will tag along with any group that will accept them, even if they have to indulge in destructive behavior in order to prove their membership in the group.

Thus, if you are seeking to curb an addiction, you need to learn how to spend time by yourself constructively, without desperation. This ability, in turn, requires several skills or resources. For example, in order to enjoy spending time alone, you must learn to calm yourself down, rather than look to other people to calm you. The skills to achieve calmness can be found through a number of approaches, such as yoga, meditation, and other relaxation or centering techniques. If you are not into developing techniques for being alone, then engage in ordinary positive activities such as walking, exercising, reading, selected television viewing (recognizing that using television as your main companion is itself addictive), hobbies, and writing letters or e-mails to real people in your life.

In addition to the skill of relaxing and centering yourself, you need certain resources, without which it is not possible to maintain an independent, self-respecting life. These independence-supporting resources include structure, interests, healthfulness, and contentment. As you develop these basic life resources, you will be better able to spend time alone and to select your company on a more positive basis.

Finally, seeing yourself as someone with a respectable and responsible life, one that you can look at with pride, is fundamental to your self-esteem. Your confidence that you have created a reasonable, positive life for yourself will strengthen you even as you seek further fulfillment and larger satisfactions in life.

5.2.4. Dealing with Negative Emotions

Addictive behavior is often triggered by a negative event that leads to depression, anxiety, or anger. These negative events are bound to occur from time to time in any person’s life, but they do not have to lead to harmful behavior. Your ability to deal with emotional upsets in a healthy, functional way is critical to eliminating addiction.

Psychologists have developed therapeutic techniques to deal with emotions such as anger, anxiety, and depression. These techniques (called cognitive-behavioral therapy) involve changing the way that you think about and react to an emotion-arousing occurrence.

The first step is to identify predictable situations that create the negative emotions with which you must cope. Does being with certain people always make you feel rejected or negative about yourself? Do certain situations always lead to arguments and anger with your spouse? Do you always have a negative reaction when a certain co-worker tries to one-up you or an acquaintance jokingly puts you down? Do you drink or overeat when you have had a difficult day at work, or when you are lonely and bored? To be forewarned about these situations is to be forearmed.

With an emotional reaction, reframing—changing how you think about an event—is critical. Reframing in this case means defusing your immediate emotional reaction by casting it in a different light. For example, when you are angered by the actions of a family member, you can keep in mind that you have responded emotionally before and gotten over it, because you realize this person loves you and is not intentionally trying to hurt you. You might say to yourself, “It’s just his way of dealing with his stress—it has nothing to do with me.” By activating this thinking as soon as an emotion-arousing event occurs, you can sidestep your emotional upset and avoid lashing out.

Once you have reframed the emotional event, you can then develop a new pattern for dealing with it.

Rather than expressing uncontrolled anger or turning on your heel and storming out, you can develop various ways to bide your time until your anger subsides and you are in a better place to respond. This may mean simply counting to ten, or else standing in place with a smile.

Changing your initial reactions as much as possible is followed by deeper changes in coping with your feelings and the things that set them off. Since these often involve people, such changes call into play your communication skills. That is, if a co-worker or family member regularly makes you feel bad with comments that you interpret as put-downs, take a moment with that person to describe how such comments make you feel, and ask the person please not to say those things.

In addition to addressing the sources of your anger, where possible, you need to find new outlets for venting your feelings more constructively. What else could you do to let off steam after a difficult day at work or being angered by a co-worker? Physical activity is one ready alternative. You could go to the gym or do a relaxation exercise. When you are bored, you can make taking a walk your patterned response. You are then killing two birds at once—dealing with feelings and gaining physical fitness.

Now that you have started to develop alternative ways of dealing with stress, anger, and other negative feelings, you can examine your coping strategies in a calm, rational way. What coping strategies have worked for you? What kinds of negative emotions are still limiting your recovery process? The longer you practice your new approach to managing your emotions, the more effective this process will become. Your coping skills will continue to grow as you practice your ability to deal with yourself in trying situations.

5.2.5. Resisting Urge

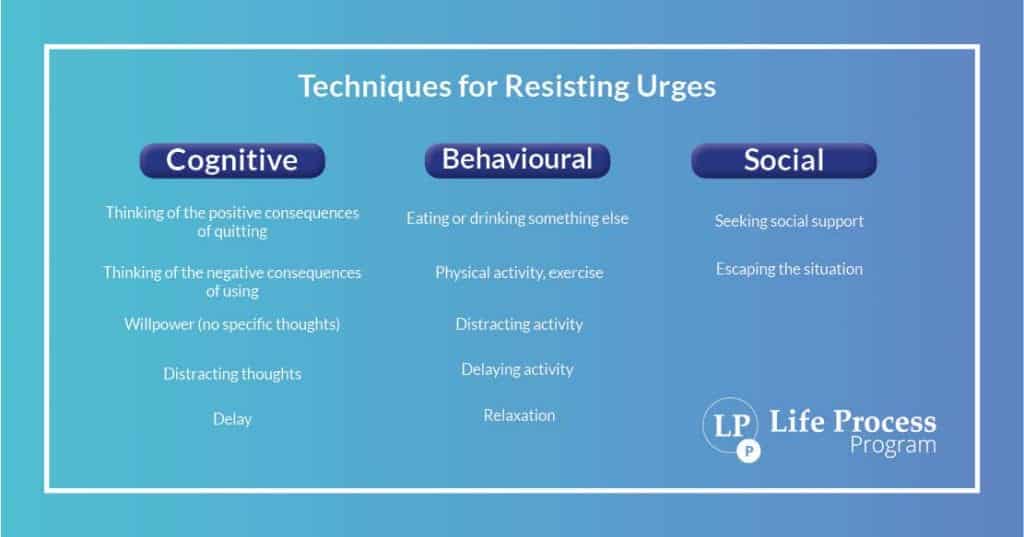

There are many different ways to resist addictive urges. In one study, psychologist Saul Shiffman studied the techniques to resist cravings for tobacco by people who had overcome nicotine addictions. He classified these techniques into three different approaches: cognitive, behavioral, and social. People utilizing each approach all managed to resist addictive urges, but each group did so in its own way.

For example, people with a cognitive approach thought through the negative consequences of their addiction. They thought through the positive benefits of quitting (as we described in the last module). They used techniques such as willpower, distracting thoughts, and delayed gratification to resist the addictive impulse.

Similarly, people with a behavioral approach resisted the addictive impulse by eating or drinking something else. They also turned to relaxation techniques, physical activity, and distracting or delaying activities to shore up their resistance.

In the third category, people with a social approach turned to others for support and took themselves out of harmful settings in order to resist addiction.

Shiffman discovered that each of these techniques for resisting the urge to smoke was equally effective. In fact, the only technique that he found to be ineffective was self-punitive thinking. Getting down on yourself for things you did or did not do was simply no help. But any kind of can-do approach—be it cognitive, behavioral, or social—worked to shore up resistance. In other words, any technique that appeals to you can be effective, so long as the technique is empowering and not self-denigrating.

5.2.6. Breaking the Flow: Relapse Prevention

Addiction, like many other problems in life, is often cumulative. That is, after an initial misstep, you become a victim of your own inertia. In an effort to recoup your losses, you repeat the behavior, but the more you resort to the addictive behavior, the more slippery the slope becomes. One clear example, of course, is gambling, where “throwing good money after bad” literally describes what you are doing. But the same is true for all addictions. Stopping the momentum toward addiction is a teachable skill called “relapse prevention.”

Relapse is not an unfortunate event that happens to you; it is a series of bad choices that you make.

Components of relapse prevention include skills we have already reviewed, such as identifying and preparing for (or avoiding) high risk situations—those in which you know you are likely to engage in the behavior you wish to cease. It involves developing alternative responses to situations you cannot avoid that cause you stress and that lead to other negative emotions.

Relapse prevention means developing backups to your plan to beat addiction. The key is to realize that even if you slip, you do not have to descend in a free fall to a complete relapse. This can be the problem with a confrontational, abstinence-only approach. If there is no tolerance for a slip or mistake, your feeling is likely to be that you might as well go all the way after one mistake—no distinction is made between having a beer, getting rip-roaring drunk, or going on a week-long bender. In addition, since even a small slip is viewed in such a negative light, your bad feelings about the slip magnify the transgression, adding guilt to the bad effects of your relapse.

Although relapse is an issue you must address, remember that a slip is not an excuse to abandon all restraint. The alternative is to recognize you have the ability to immediately regain control after a slip: “I just mistakenly had a drink (or even several); I will resume my abstinence.” If you are a food addict (compulsive eater) and eat a whole bag of chips, you should not take this as a signal to go ahead and binge for the rest of the day, week, or month.

Your emotional and practical planning are the keys to avoiding these further steps to all-out binges. First, try not to get so down on yourself that further excess becomes your only refuge from self-loathing and despair. Second, whenever you feel yourself sliding out of control, remember that you have a choice. If you wish to escape, then you can pull yourself out of the turbulence.

6. Support: Getting Help from Those Nearest You

The process of learning from others is called “social learning,” or “social influence.” Its critical importance is one of the fundamental realities that contradict the disease view of addiction. That is, accepting the social sources of control and excess means that people’s biological reactions are not the root of addiction to alcohol, drugs, gambling, or food. And if social influence is the most powerful determinant of reactions to drugs and other addictive sensations or experiences, then it can also be the most powerful tool for preventing or recovering from these addictions.

There are many ways in which people can help you to beat addiction and change behavior. You can enlist others to help motivate and support change. You may choose to associate with people who don’t engage in the activity or who do so in a moderate way.

We have all witnessed the effect of social interaction and influence on substance use, intoxication, and addiction. You know, for instance, that when you are with certain friends you are more likely to do things you regret, like overeating, smoking, or drinking too much. You know that you behave differently when you are with other friends who either don’t indulge in these behaviors at all or do so moderately.

Social factors are the most potent determinants of addiction, but they can also be harnessed as a tool for recovery. The ways to do this include (1) finding people and groups to support your recovery, (2) working with the significant others in your life so that they become a supportive force to reduce the pressures that lead you to succumb to your addiction and thus enhance your chances for recovery, and (3) playing the same positive role for others as a friend, spouse, or participant in a group.

6.1. Using Support Groups for Sobriety

Among the most straightforward things you can do to lick an addiction is to shift social groups. Special-interest groups, community involvement, or church groups offer time-proven ways to change your social network. Dedicated support groups such as SMART Recovery and Moderation Management (MM), as well as the Life Process Program online community.

Twelve-step groups (such as AA and NA) are not our first recommendation because they perpetuate a mentality of powerlessness. When such groups do succeed, they do so in good part by creating non-drinking/non-using social networks for their participants. But there are downsides to such social support networks as well. The problem may occur when, in joining AA, NA, or a similar program, you isolate yourself from others outside the group. Some members or groups may actually insist that you should now associate mainly with your fellow twelve-step group members. As part of this focus on the group, you learn a way of thinking and expressing yourself that often leaves others out in the cold. For example, you use code words and concepts—“friend of Bill’s” (referring to one of the founders of AA), “one day at a time,” “serenity prayer,” and “dry drunk”—that non-AA members don’t understand or respond to. In finding support in groups or activities,your goal should be to continue to work with those close to you to avoid simultaneously losing other primary supportive relationships in your life.

Have you spent time—perhaps quite a bit of time—in Alcoholics Anonymous? What has that been like? Was it overall a positive experience? Did you find it easy to identify with fellow AA members? Or was their pre-occupation with drinking—and avoiding it—off-putting for you? Did you form relationships that then turned out to be disappointing or disillusioning? Did you find members hypocrites (for example, did you suspect—or know—that some of them were drinking)? Did older members try to pull rank on you?

You might answer the questions above both positively and negatively. That is the nature of dealing with people and groups—you take the good with the bad. The question is whether you can do better, either by eliminating or reducing your reliance on AA, and/or by seeking other forms of healthy support networks.

Closing off your life to non-addicts is a steep price to pay for quitting your addiction. Whether or not you join a support group for substance abusers, you need to continue to balance your life with other social supports for sobriety and change. There are people and places to turn to for support in quitting your addiction other than those in addiction support groups. One option is to surround yourself with people who are not addicted and never have been. These may simply be people who don’t drink (or who drink moderately), don’t smoke, don’t gamble, and so on, and who are fully involved in life, work, and other positive activities. In doing so, you replace the unhealthy and excessive groups with which you have been associating with people who will model moderate and constructive behavior.

6.2. Creating Support Networks

Another option for locating the support you need to change your behavior is to form your own group among people you know with needs similar to yours. For example, many people exercise with friends. Groups of like-minded people bicycle and run together on weekends or walk with neighbors during the day. In this approach, while changing your behavior you associate with people you already know and like to spend time with—people whose goals and expectations are similar to your own.

With the advent of the Internet, many people find their support groups far and wide, as like-minded people or those with similar problems, no matter how rare, can be brought together over broad distances. For some common problems, such groups are ready-made. It is very reassuring to conceive of a large group of supportive people out there, even if you never actually meet them.

6.3. Family as a Support Group

In most cases you don’t want to stop associating with your friends or family in order to change your behavior. The fact is that your family, friends, and business associates are often a big part of the reason why you were moved to quit your addiction in the first place. Having those nearest to you disapprove of your behavior can cause difficulties in a relationship, but this opposition is also a hugely motivating force, one that can be harnessed for change.

Your loved ones are always around to remind you why you quit in the first place. Marriage and intimate relationships are so critical to the recovery process that the Community Reinforcement

Approach creates a buddy system for those who don’t have a spouse or other intimate. Since people often share problems with those close to them, a logical step may be to attempt to change together. For example, spouses often quit smoking, lose weight, reduce alcohol consumption, or work together to eliminate other addictions.

Those Closest to You Are Your Biggest Help, and Your Greatest Burden

As Mike’s experiences illustrate, your family can be one of your best support networks. After all, they are available to you twenty-four hours a day, they know you intimately, and they have an interest in your well-being. However, the same people who can help you kick your addiction can also keep you on your addictive course. Sometimes a person’s dissatisfaction with a spouse is the immediate stimulus to return to smoking, a night of drinking, or binging on pornography.

Maintaining a healthy relationship overall requires that you know how to negotiate with your partner. You need to be able to express your needs reasonably and to be forthcoming in fulfilling the other person’s needs. If you give too much or too little, or feel perpetually used or ignored, you cannot comfortably relate to other people. This truism is especially evident in the area of addiction.

6.4. Codependency

At the other extreme from focusing together on a shared goal of change are cases where an intimate relationship is based on one partner’s addiction. The less obviously addicted spouse feels needed by the more obviously addicted spouse and thus more valuable as a person. In these instances, an addicted person’s partner may actually sabotage attempts to change an addictive habit. Insecure about her own attractiveness or her role in her partner’s life, this spouse may feel that the less attractive the addicted partner is to the outside world, the more dependent he will be on her. Who else would be able to put up with his addiction? This is a common dynamic with a people addicted to drugs and alcohol and their partners. If you find yourself in one of these situations, then fighting your addiction may mean you need to re-evaluate or even end your relationship. Certainly you need to change the way you deal with your partner and the lifestyle you’re accustomed to together.

6.5. You Create Your Own World

Earlier we discussed how critical group pressures are in eating, drug use, and attitudes toward alcohol. This has the slightly pessimistic impact of suggesting that you are doomed to suffer from whatever problems afflict your own social group. In other words, if American attitudes toward drugs and alcohol are screwed up, how can you do any better on your own?

The best strategy is to create your own small culture of health and responsibility—at work, at home, or elsewhere. Every human being can succeed in modifying his or her own thinking, behavior, social reality, and life course. In order to succeed, you must select from and reshape your social environment to support the positive changes you want to make. These changes are in keeping with who you believe you are and who you want to be.

Exercise 1: Emulate Successful Friends

Think of five people you know whose behavior in the area of your addiction you most admire or want to emulate. How can you spend time with them, especially engaging in the behavior you want to change? Can you ask them directly for suggestions for how they manage in this area (this is often called coaching)? They will be flattered and will know that you are interested in improving. They thus become part of your change support group.

Exercise 2: Inspect Your Relationships

List your five closest relationships. How does each one support your bad habit or addiction?

- How does each offer leverage against your negative habit?

- Which of these relationships would you be better off leaving behind to overcome your addiction?

- Which of these relationships can be modified to support changing your addiction?

- What needs to take place in these relationships to shift their balance from possibly supporting your addiction to helping you beat addiction?

- Think of one thing to do about each of these relationships, and do it, telling the person in each case what you are doing and why. Involve that person, where possible, in the discussion.

7. Maturity – Growing into Self-respect and Responsibility

ADDICTION is a search for immature gratifications—it is an over-concentration on oneself resembling that of a dependent child. As a result, overcoming addiction requires growing up and assuming adult roles. In this process you learn to take responsibility not only for yourself and your own behavior but for other people in your life. One natural outgrowth of this mature outlook is that you may no longer see yourself as powerless or label yourself an addict. You may no longer feel any need for the addiction, so it ceases to have any presence in your life.

The addiction field has an evocative term for this phenomenon—maturing out. Many people once addicted to heroin or other so-called “hard drugs” often use this term. The typical reason former heroin habitues give for outgrowing their addiction is that they are tired of the lifestyle—being on the outside, being cut off from normal life, the constant hustling and evading the law, the absence of anything new or better stretching out before them.

Certainly, maturing out is not limited to heroin; it happens with all addictions, including alcohol, sex, and gambling. As you mature, you become dissatisfied with your limitations. You develop more connections to life, through marriage, parenthood, or career accomplishments. While undergoing these external developments, you simultaneously experience critical internal emotional changes. At the same time, your self-image and identity change.

7.1. Gaining a Positive Identity

To mature, you need to do more than simply get older—you also need to experience life and learn its lessons. At some point—actually, at various points—in your life, you decide who you are, that is, what your identity is.

Many in traditional addiction treatment feel that people must accept that they are lifelong addicts— that no changes they undergo or create for themselves will ever allow them to escape this identity.

In their view, it is dangerous—a matter of tempting fate—to say that you are fully recovered. The LPP takes a different tack. We want you to know that there is no reason you can’t change who you are, including your “addict” identity, with alcohol, drugs, or anything. It may be take time, but carrying the baggage that you must always (or ever) think of yourself as an alcoholic or drug addict will only weigh down your recovery effort.

7.2. An Everyday Example of Maturing Out

Nicotine is a more commonplace drug than heroin, yet it is as potent and as harmful as any other drug addiction. People usually get addicted to cigarettes in their teens and twenties. At this age they are anxious about their identities, eager to fit in, and do not yet detect any signs of physical problems due to smoking. As time proceeds and smokers take on families, jobs, and positions in the community, the forces fighting against the addiction add up and eventually outweigh the value and satisfaction of continuing the habit. Today, one of the primary reasons for quitting is that smokers face so much social pressure that they are in danger of becoming pariahs.

7.3. Emotional Maturity

Maturity means turning away from a preoccupation with your own needs and becoming aware of the needs of the people around you. Along with abilities and assets that you gain with age, you also gain faith in yourself, patience with others, and self-awareness—a kind of overall equilibrium. This does not mean that you become perfect or that you shed the personal traits, both positive and negative, that distinguish you from others. But it often means that you are more forgiving of yourself as well as of others. Maturity changes the way that we experience and react to different events in our lives

When you are able to control your reactions, or overreactions, you are less likely to need to resort to addictive remedies. In the first place, you experience fewer of the negative emotions, such as anxiety and depression, which impel addictions. In the second place, you feel more confident about being able to meet and overcome challenges. And third, even when you are not able to resolve an issue fully, you are more accepting of yourself and the situation. Age helps beat addiction in that it bring to light the fact that a lot of emotional turmoil, and the addiction that goes along with it, is unnecessary.

7.4. Responsibility